What’s in a legacy? Part 1 – Small acts to make a big impact

For your NC3Rs funding application to be competitive it must include a strong plan to achieve a lasting 3Rs legacy. But what is a 3Rs legacy, and how do you show a panel you’ve considered yours?

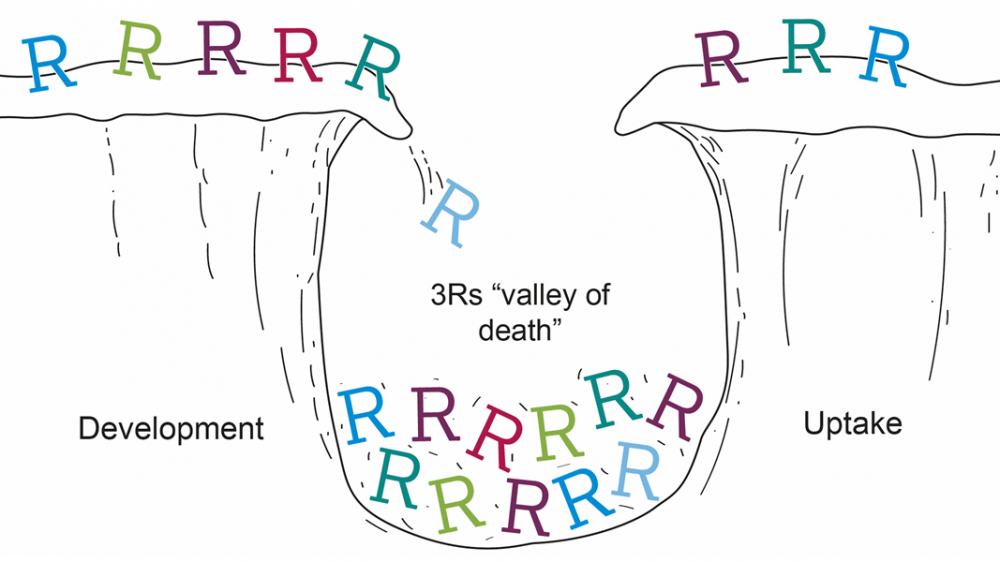

A 3Rs method, tool or technology must be taken up outside the lab that developed it to achieve full impact, whether that is other labs in the same institution, the UK or worldwide. A method or tool that does not achieve this is a real missed opportunity for the 3Rs. Some 3Rs models struggle to overcome this hurdle, falling into what we have termed the ‘3Rs valley of death’.

This does not need to be the case. Some careful planning, and insight into who your end-users are can help you to identify the best way to target your communications with them. This can help encourage and achieve uptake, ensuring your 3Rs method does not stop at your lab. By providing these details in your application you can demonstrate to the Panel you have a clear and reasonable dissemination plan tailored to your research needs.

In this blog series, we will be speaking to some of our grant holders to ask them how they planned their 3Rs legacy to be realistic and sustainable and how their 3Rs legacy has helped further their own research.

Dr Alasdair Nisbet – Moredun Research Institute

Alasdair was awarded an NC3Rs Project grant in 2017 to develop and optimise a device that improves the testing of treatments against poultry red mites, reducing the number of hens used in field trials. The ‘on-hen’ device requires four hens per treatment group compared to 400 per group in a field trial. To date the device has been used to provide data that has prevented seven unsuccessful vaccine candidates and vaccine delivery methods from going into field trials, which would have used almost 5,500 birds. The initial pre-screening using the on-hen device exposed hens to 100 mites for three periods of three hours – the field studies would have exposed birds to more than 10,000 mites for 100 days, affecting hen welfare through irritation and anaemia.

Now Alasdair's Project grant has completed, we caught up with him about how he planned his 3Rs legacy, the impacts on his research and how small acts can contribute to a lasting legacy.

Start by recognising key requirements

I still clearly remember when I decided to investigate developing the on-hen device. It was after a disappointing finish to a field trial that used 800 hens on what proved to be a non-efficacious vaccine. We perform initial vaccine testing in vitro but the results are often not reflective of field trial results and at the time there was no obvious in-between stage.

I was aware of previous work into on-hen devices, but also knew these did not achieve much uptake within the red mite research community. The devices only allowed one stage of mite to feed, which was a big drawback as vaccine targets may be present in one or more of the three mite development stages. The devices were also rigid, which often led to failures of mite feeding because the device didn’t attach well to the contours of the hen’s skin and body. So, for our device to be different and not fall down where previous work had, I knew it had to be low cost, flexible, contain the mites for the period of testing, and be compatible for use with each of the developmental stages for other researchers to be interested.

Identifying these key requirements ahead of time meant we could be confident our method would have practical utility and appeal to researchers in the community with as few barriers to uptake as possible.

Develop a robust response for naysayers

At the beginning of the project, there were some people we spoke to who didn’t believe the on-hen device could or would ever work, including some members of the Animal Welfare Ethical Review Body (AWERB) at Moredun. I do not believe this is a bad thing though as having people question the work meant we could address limitations early in the development process and have a robust response to convince others of the method’s potential.

For example, one of the more frequent comments we received was that regulators would never accept data from the on-hen device as evidence of vaccine efficacy or effectiveness of any other anti-mite products. To be able to counter this viewpoint, I contacted regulators we would be approaching in the future to explain what we were trying to achieve. While they could not give a definitive response without seeing the data, the regulatory body did confirm they were interested in the innovative method and its potential to reduce the number of animals in trials.

Having conversations like these along the way highlights any issues or potential areas of concern that need to be explored before wider uptake in the research community is possible.

Present the method itself at conferences

Like many labs, we used to mainly present new data at conferences. We took a different approach with the on-hen device and began presenting the method itself and we did this early, before we had much scientific data that we could publish. The presentations were well received by the community, and Dr Francesca Nunn, the postdoctoral researcher working on the project, got a lot of contacts from people interested in the technique, including from people who worked with other parasites in hens, and groups who research parasites in mice – all wanted to see if they could apply the method.

I’m keen to do this with other research now and find that the presentations I enjoy most at conferences are the ones presenting new methods and technologies. It makes me wonder how I can apply that cool new technique to my own research.

Watch this demonstration of the feeding device assembly, application of the device to hens, and device removal.

Make the most of your existing networks…

We are very lucky in my group to have an existing network of collaborators through a European project. I made sure to make the most of this network when starting to disseminate the device and hosted some of my collaborator’s PhD students, who then took the method back to their own labs to set up. This gave us a place to start to learn how to teach others to use the device and what problems people may come across when setting up the method in their own lab.

… but don’t be afraid to make new ones!

We emailed the main labs we knew of working on poultry red mites inviting them to a workshop to learn about the construction and use of the on-hen device through our NC3Rs Skills and Knowledge Transfer (SKT) award. However, we also made sure to ask if there were any research groups we had inadvertently missed. The other thing the SKT award encouraged me to do was to reach out to labs I might have once considered a competitor. It felt in the ethos of the 3Rs, knowing that the on-hen device had the potential for reduction and refinement impacts in their labs as well.

We received a lot of interest from the community and established new collaborations that are still ongoing that we might have never begun before the on-hen device project.

And keep a look out for the opportunities a new method can bring

Now, at the end of the grant cycle, our focus for the on-hen device has shifted away from optimising and towards its immediate practical applications in our research strategy. My PhD students are using the method in their projects and the method is now a regular part of my grant applications. With commercial partners we have used the device to test novel vaccines and formulations of vaccines and have also had discussions with major animal health companies about using the device to test new acaricides on a small scale before progressing to larger trials.

Alongside our scientific publications, we also have methodology papers describing the on-hen device. Publishing these detailed methods in a stepwise manner helps aid the uptake in the wider scientific community. We were also able to prove, and publish, an anecdotal observation long noted in the field that mites were unable to feed as easily on aged hens.

And now, we’re about to start this journey again as we have recently been awarded another NC3Rs Project grant, not relating to the on-hen device as this has gained enough momentum to ensure a sustained 3Rs impact. Rather this new grant focuses on the production of red poultry mites using large scale in vitro culture to provide consistent batches of parasites for research purposes. This is usually done by infesting donor hens and is of course associated with serious welfare concerns. We have good evidence that mites will feed on blood in vitro and so with our new award we aim to expand on this preliminary data to further improve hen welfare in research programmes.

Read more about Alasdair’s NC3Rs-funded awards, and see Francesca present the research after jointly winning the 2019 International 3Rs Prize.

For more information on applying to the NC3Rs for funding, please see the Grants and funding pages for descriptions of our response mode funding schemes.