Changing mouse handling practice at a university establishment

Lesley Gilmour is the University of Glasgow’s Named Training and Competency Officer (NTCO), responsible for ensuring that all those working with animals are appropriately trained, supervised and competent.

In this blog post, she shares her experience of implementing refined mouse handling across the institution, including some top tips.

In August 2017 I took up the position of NTCO at the University of Glasgow. I was mostly excited and motivated by the prospect of how I could shape this role and what could be achieved to improve our culture of care. Admittedly though, some of my objectives did feel rather mammoth to tackle. One such objective on my “to-do list” was implementing the use of non-aversive handling methods for mice across the University. Like many other Universities, Glasgow has a lot of Project and Personal Licence holders working in different research areas, as well as in multiple animal facilities spread across the campus. Furthermore, the budget for resources was very limited, making it difficult to know where to start. This blog post details the strategy I have used to improve the uptake of refined handling methods at Glasgow and my journey so far.

The lie of the land. The first thing I did was to try and get a better idea of how researchers and staff were actually handling mice, by sending out a short questionnaire. Nine percent of people who replied said that they exclusively used non-aversive methods, 53% used a mixture of non-aversive and tail-handling, and 38% exclusively tail-handled mice.

Get your animal care staff on board. I view our animal care staff as role models for those working with laboratory animals. Therefore, I believed that for researchers to take this seriously, it was vital for our care staff to be seen using refined handling. We discussed the topic during staff meetings and I listened to their concerns and ideas.

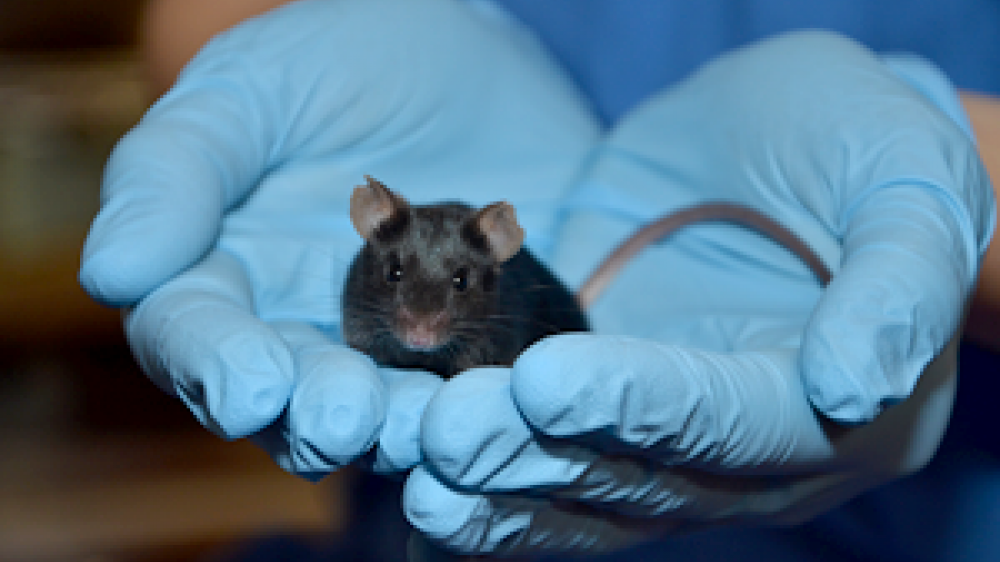

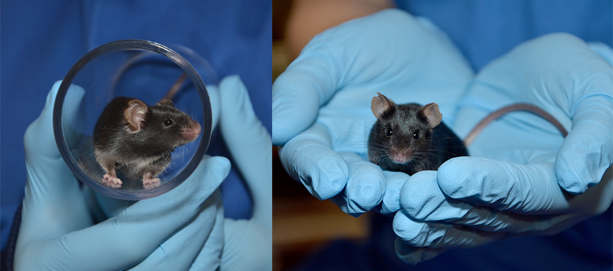

Address concerns about change. Both animal care staff and researchers had similar concerns and one of them was time. Many people speculated it would take too long to change cages, wean mice or remove an animal from a cage for a procedure if it could not be picked up by the tail. Another concern was that “jumpy” strains of mice would not be amenable to tunnel or cup handling. To investigate both these concerns in-house, I organised two studies – a time challenge and a jumpy strain habituation challenge. For the time challenge, I enlisted the help of one member of animal care staff in each unit to record the time taken to move animals from their home cage, and back again, using tunnel versus tail handling. This was repeated for ten cages (each handling method) over four weeks. We found that it took marginally longer to move mice using a tunnel initially; but there was virtually no difference by week four between tunnel and tail handling. For the jumpy strain habituation challenge, I trialled refined handling on weanlings of a notoriously jumpy strain (they jump out of the cage when given the chance) and made video recordings of the handling sessions. The mice were removed from the cage once per day using a tunnel. By day eight, not only were the mice habituated to the tunnel and happy to be taken out of the cage, but they were tame enough to be cup-handled. This behaviour was dramatically different to age-matched, tail-handled mice of the same strain.

Even jumpy strains can become habituated to refined mouse handling methods.

Make tail-handling by exemption only. Despite offering training and demonstrating that refined mouse handling methods could be used across the University, a number of people still insisted on tail-handling. Inertia was evidently a problem amongst some groups, so I felt the most obvious way to significantly change practice was to get high-level support and introduce a policy on mouse handling. In February 2019 an NVS colleague and I formed an AWERB Culture of Care Subgroup. The topic of our first meeting was a proposed strategy for implementing non-aversive handling across the University, and we told staff and researchers our intention to take this to the main AWERB and ask for endorsement. We were successful and in April 2019 the AWERB and establishment Licence holder released a policy statement on handling of laboratory mice, stating that “Non-aversive handling methods should be used as standard practice in all situations where a mouse has to be captured and removed from the cage. This includes during routine husbandry, health checking, killing by schedule 1 and prior to restraint of an animal to perform a procedure. Mice should not be captured and removed from the cage using the tail. The tail may be handled during restraint of a mouse after removal from the cage”. This made non-aversive handling compulsory, and those who wished to tail-handle had to seek exemption from the AWERB.

Provide continued support. Although non-aversive handling is now compulsory at the University, I still believe that changing practice will only be successful long-term if continuous help, support and encouragement is provided. It is important that researchers talk openly about the challenges they face when using refined handling so we can try and address these together, rather than everyone pretending things are working well if they’re not. To support researchers, I provide small group training sessions using their own mice to go over the basics of tunnel handling (which I believe to be the foundation level of non-aversive handling). During the session we talk specifically about what procedures they perform and perceived difficulties they might have. These sessions are also a good opportunity to remind people that the more frequently they handle their animals, the better the experience for both handler and mouse. Investing just a little more time into handling mice can completely change their temperament, as shown by my jumpy mouse habituation challenge. After the training session, each person’s skills and understanding of tunnel handling are assessed. We started these training sessions in June 2019 and usually hold one to two per week. I estimate it will take at least 18 months before everyone is trained, but I believe that this personalised approach will be more likely to ensure a lasting change in mind-set and practice.

Evaluation. Much of the positive feedback I’ve had up until now on switching handling methods is anecdotal with people noticing a decrease in mouse stress levels, making the handlers’ interaction with the animals easier. This observation is encouraging, but an evidence base is needed in order to convince more scientists. In collaboration with the researchers, we are looking at control data collected pre- and post-switching to refined handling, in order to identify any changes; for example, changes in standard deviation could provide information on changes in variability. Finally, I plan to send out a follow up questionnaire a year on from when the handling policy was introduced to assess what impact the efforts of the past year have made and areas where more attention is required.

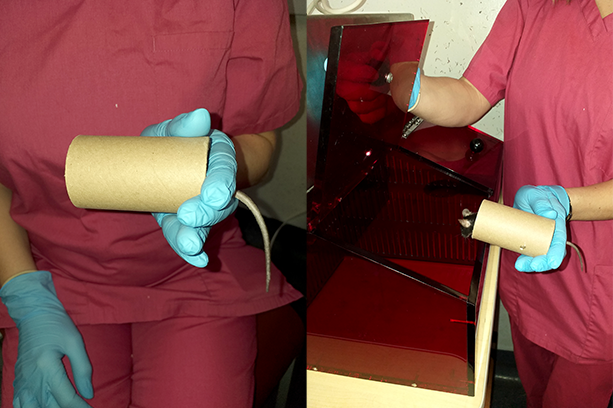

We sometimes restrain the mouse's tail while it is in the tunnel to prevent it jumping out. This is useful when you can only use one hand, e.g. when opening chambers.

Top tips. I don’t think there is a “one-size fits all” strategy when it comes to introducing change of any kind of practice, but there will be common challenges to overcome. These are my top tips that I believe would be helpful to anyone trying to introduce a change in handling methods.

- Ask yourself “do I believe in it”? If you are going to be the spokesperson driving forward this change, then you have got to understand the reasons behind it and believe in it yourself. If you don’t, then you won’t stand a chance against the critics. I did believe the data in the literature and that changing handling practice would improve animal welfare. However, by doing the jumpy mouse habituation challenge myself, I really cemented those beliefs.

- Identify your champions. This is not a one-person job! You will need people who can provide practical help with training. Like you, they should also believe in the reasons for change. As handling is not a regulated procedure, un-licensed animal care staff can help with time and habituation challenges, training and assessment. So far, those I’ve worked with to implement refined handling at the University of Glasgow have enjoyed being part of such a big initiative. Throughout this journey I have experienced many periods of negativity – times like this are when it is really important to have a conversation with your champions and other like-minded people, to get support and remind yourself why you are doing it!

- Tackling inertia and an unwillingness to change attitude. It is important to listen to those who have specific concerns about change and aim to address these. I’ve found that the best way for me to tackle resistance is to ask for specific reasons why an individual does not want to use refined methods – we no longer accept time as a reason! Moreover, the best place to ask this question is during a practical group handling session where said individual can demonstrate the issue, rather than in a meeting or seminar environment. Then I can witness for myself the challenges different people may face and identify cases where inertia may be the only reason someone is not willing to change their practice.

- Seek high level support. AWERB and establishment endorsement has made more people willing to listen and has helped with getting the unwilling to co-operate. It can also be worthwhile to remind personal licence holders of their responsibilities and the standard conditions of holding their personal licence: “In exercising his or her responsibilities, the licence holder should act at all times in a manner that is consistent with the principles of replacement, reduction and refinement”.

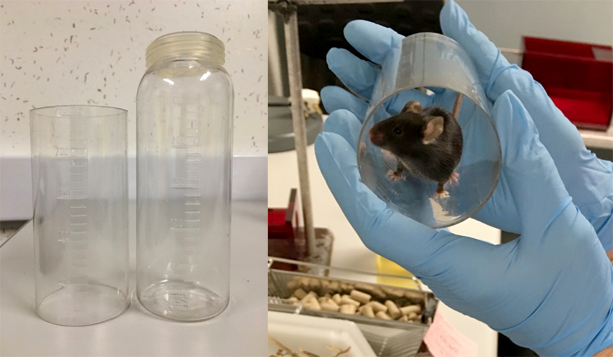

- Improvise. As I mentioned, we had very little money to buy resources for tunnel handling. We already used cardboard tunnels for enrichment in the cages, so we used these instead of plastic handling tunnels. A member of staff also came up with the genius idea of trimming and sanding down a load of old plastic water bottles to turn them into tunnels, which worked really well!

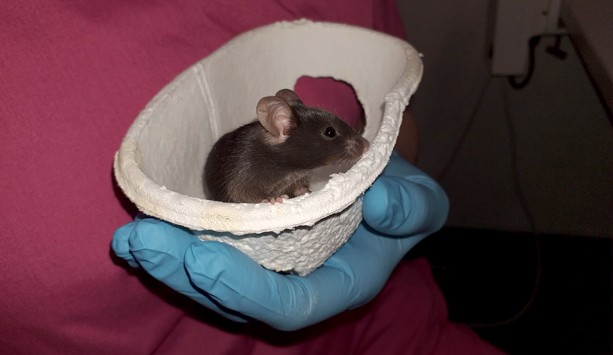

- Don’t be too prescriptive. During handling training sessions, I explain to people that the focus is to avoid picking up the mice by the tail, but it is up to them to choose the refined method they want to adapt to achieve this. We also offer a range of handling props. Lots of people prefer the cardboard tunnels as the mice are already familiar with them, but we have people using plastic tunnels, dome homes (as scoops) or cupped hands. With regards to technique, I do give some general pointers to start with that I got from the handling videos on the NC3Rs website. Other than that, I don’t offer too many specific pointers, just to avoid overcomplicating things.

Old plastic water bottles can be recycled into tunnels to cut down on costs and resources.

Dome homes can also be used to "scoop up" mice.

Find out more about non-aversive mouse handling via the NC3Rs ‘How to pick up a mouse’ resource hub, featuring the evidence base, video tutorials, frequently asked questions, and more.

Videos

Habituation – day 1

Habituation – day 8

Beyond the habituation period for tunnel handling

Beyond the habituation period for cup handling