Efficient transport box and chair training of rhesus macaques

A new paper published today in Journal of Neuroscience Methods documents refinements in how rhesus macaques used in fundamental neuroscience research are trained to enter transport devices.

Neuroscience experiments typically involve macaques undergoing testing on cognitive and behavioural tasks in the laboratory, often with electrophysiological recording of brain activity or neuroimaging. Methods used to transfer the monkeys to the experimental set-up, and the time involved in training for cooperation with this potentially stressful procedure, can vary a great deal between institutions but may take many months.

In the new publication, Dr Anna Mitchell and colleagues at the University of Oxford and KU Leuven in Belgium report refined methods developed to train monkeys to enter transport devices voluntarily and without restraint via the ‘pole-and-collar’. Reliable, voluntary transfer from the home enclosure into a transport box or primate chair was achieved within only ten days. Those monkeys requiring neck restraint as part of the experimental protocol were trained to voluntarily present their head through the chair aperture for neck-plating within a further ten days.

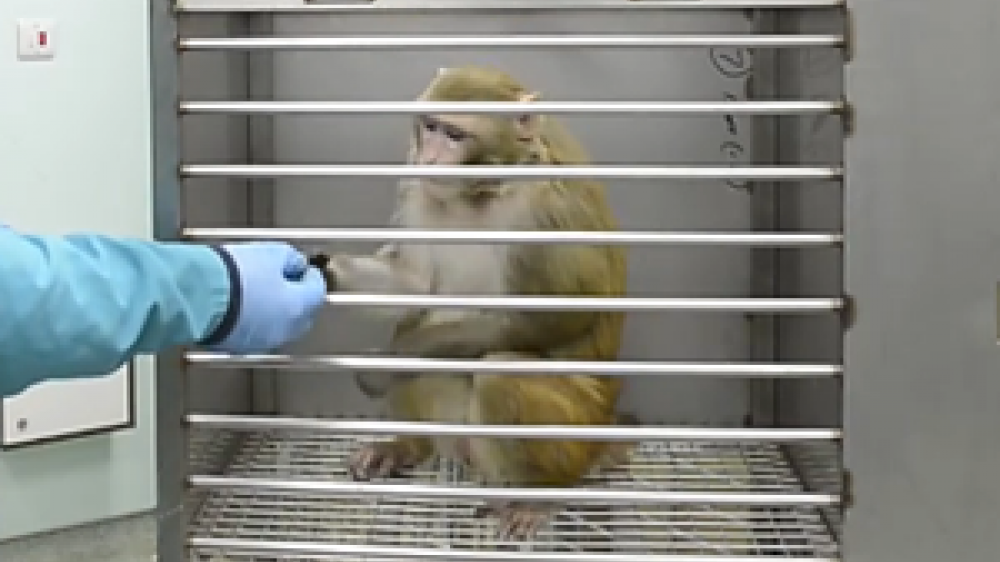

Monkey exiting the home cage into a transport box (NC3Rs Macaque Website)

In both cases, the training was based predominantly on positive reinforcement techniques (PRT) with limited use of negative reinforcement (NRT). Desired behaviours performed during training were rewarded with preferred treats (e.g. peanuts, dates, diluted juice), while the animal’s main ration of calorific mash and fruit was withheld until the end of the daily task training session. For some monkeys, to ensure they could progress in the training programme, NRT such as the cage squeeze-back mechanism or space-reducing panels within the modified chair had to be used to facilitate exiting from the home cage or head presentation for neck-plating.

Mr Stuart Mason, first author and main primate trainer, said: “In our experience, PRT techniques work well for most monkeys and create a positive relationship between trainer and monkey. Where NRT techniques are required in addition, they should only be used for short, quick periods of time to be effective.”

Adjusting the space-reducing panels in the primate chair (University of Oxford)

The authors were able to retrospectively analyse training records for 46 male rhesus macaques used in neuroscience experiments over a nine-year period. Training the monkeys in pairs or groups and starting their training upon arrival within the primate unit were both found to reduce the time required to acclimate them to the transport box/chair.

Because the monkeys progressed in their training more quickly, they could engage with the neuroscience research sooner. The authors conclude that these training refinements can potentially reduce the total time monkeys need to spend in an experimental setting or allow more data to be collected over a fixed time-period, benefiting science and animal welfare.

The monkeys that participated in the research were funded from MRC and Wellcome Trust awards to Dr Mitchell. The NC3Rs has supported Dr Mitchell and Mr Mason to disseminate the refined methods to other UK laboratories. See the NC3Rs website for further information on training using positive reinforcement, food control and chair restraint.

References

-

Mason S, Premereur E, Pelekanos V, et al. (2019) Effective chair training methods for neuroscience research involving rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta). Journal of Neuroscience Methods 317: 82-93. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2019.02.001