Out of the box, into the egg: a new way of studying human bone repair

A recent study has shown that human bone regeneration can be studied in the extraembryonic membrane of a developing chick egg, which could replace studies in mice.

The work, by Dr Richard Oreffo from University of Southampton and NC3Rs-funded PhD student Inés Moreno-Jiménez, has recently been published in Scientific Reports.

Understanding the mechanics of bone regeneration and repair is important for developing new treatments for disorders such as bone fracture (e.g. as a result of injury) and loss of bone tissue (e.g. in osteoporosis), both of which can result in a reduced quality of life. One treatment strategy to help bone repair is attaching biomaterial scaffolds to the repair site, providing mechanical support to guide tissue growth and elements important for bone forming such as growth factors.

There are many possible biomaterials which can be used for these scaffolds, and researchers are always in search of new options. The efficacy and safety of these materials are assessed in in vitro and in vivo models before obtaining approval for clinical applications. The in vivo models include injecting the implant within a bone cylinder subcutaneously into mice, to study the immune response and blood vessel growth, among other factors.

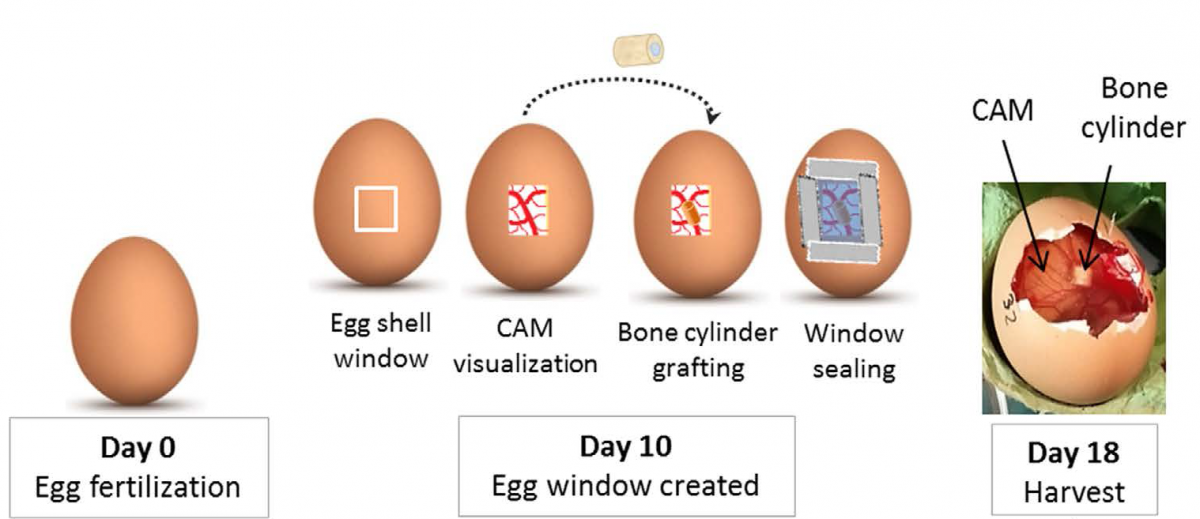

Instead of using mice, the team at the University of Southampton are investigating the use of the chorioallantoic membrane (CAM) assay, which involves implanting and incubating a material or compound on the extraembryonic membrane of the developing chick egg (see photo). Importantly, the assay is minimally invasive to the chick embryo: the CAM has blood vessels but is not innervated, so no pain is experienced by the chick.

Ms Moreno-Jiménez and colleagues developed a bone repair model using femoral head bone samples from patients undergoing orthopaedic surgery. The cylindrical bone samples were damaged by introducing a small defect with a drill. They were then grafted onto the CAM, which incubated the bone, providing a surrogate blood supply that allowed the cells to remain viable.

Using the CAM assay, the researchers were able to observe the deposition and resorption of bone tissue (signs of bone recovery) on the grafted bone. The assay can be used as a bioreactor for studying the effects of drugs and different biomaterials on bone repair without the use of mouse models, refining the use of bone injury models in research.

Inés Moreno-Jiménez finished her NC3Rs-funded PhD in September 2016. During the course of her studies, she promoted the new CAM method to colleagues during events and conferences. She was also on the FIRM (Future Investigators of Regenerative Medicine) meeting organising committee, where she organised a workshop: ‘The 3Rs in animals in research’, led by Dr Katie Lidster from the NC3Rs. She will soon begin her new role as a post-doctoral researcher with Professor Dietmar Hutmacher at Queensland University of Technology, Australia, where she plans to continue to promote the 3Rs.