Worm hunting in Colombia: fighting whipworm infection in the lab and the classroom

In February 2018, Dr María Duque-Correa, a David Sainsbury Fellow based at the Wellcome Sanger Institute, visited Colombia with a special mission: to ‘hunt’ the parasitic whipworm.

The Worm Hunters project combines public engagement and raising awareness about whipworm infection with de-worming treatment, as well as providing the opportunity to collect samples of human whipworm to study in the lab. The team worked with school children in Ciénaga, a town on the Caribbean coast of Colombia where up to 50% of children are affected by whipworm infection.

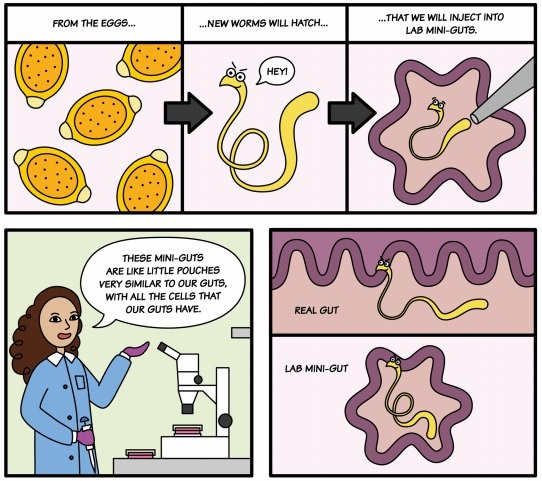

Whipworms infect approximately 700 million people globally and cause trichuriasis, a major neglected tropical disease that causes diarrhoea and anaemia and has been linked to malnutrition as well as physical and cognitive developmental problems. María’s research, funded by an NC3Rs David Sainsbury Fellowship, focuses on host interactions with whipworms in 3D intestinal organoids (mini-guts), as a strategy to replace animal use. The availability of human whipworms (Trichuris trichiura) for research is limited, so the mouse whipworm (Trichuris muris) studied in mice is currently the main tool for trichuriasis research. María has been studying the mouse whipworm in vitro using mouse-derived organoids, but her long-term objective is to develop a more human-relevant model that can maintain the human whipworm in culture.

María spoke to us about the Worm Hunters initiative.

Where did the idea for Worm Hunters come from?

My research focuses on parasitic worms, and I always wanted to work with the communities that are affected by them. Our team have already done a lot of public engagement in British schools, such as the Genome Decoders project, in which pupils from 50 schools across the UK were engaged. The students worked with scientists to help improve the understanding of the human whipworm’s genome by annotating different regions of the genome and identifying genes potentially involved during infection and disease.

That experience was fantastic, but I thought that working with children who are infected or at risk of infection might have an even bigger impact. At the same time, I was interested in doing research with the human parasites and getting the human material, which is not easy to obtain. I worked with the Public Engagement Team at Wellcome Genome Campus and the University of Antioquia to create the Worm Hunters project.

What did you do during your stay in Ciénaga?

The Worm Hunters team visited the school for a week and worked with 120 children aged seven to ten years old. We first met with the children and their parents to explain our plans, engage the community and obtain informed consent.

Over the next few days, children brought in their first stool samples to be diagnosed. The kids could also observe some of the parasites under the microscope, which they really enjoyed! The visiting doctors then de-wormed everyone who was diagnosed with any parasitic infection, regardless of their involvement in further parts of the project.

María Cristina & Dora - On sample processing (ENG captions) from Jose A Dianes on Vimeo.

We also wanted to raise awareness about common risks and routes of contamination and infection. Children received a comic book made specially for this occasion, with activities that kept them engaged for the week-long project. The comic helped us explain why they needed to bring their stool samples and what would be done with their samples in terms of further research back in Cambridge.

The hands-on activities included ‘Handshake challenge’ and ‘Contamination detectives’, which helped us demonstrate how infections can spread among people and through unwashed fruit and vegetables using a special gel visible only under UV light.

Finally, the children that had been diagnosed with whipworm were asked to donate their complete stool sample for the Worm Hunters to study in the lab. The participation rate was incredible – we received samples from all but one of the children. The worms have now been transported back to the UK where they will be part of our future experiments to understand how whipworms infect the intestines.

Wash your hands! from Jose A Dianes on Vimeo.

Do you think the children enjoyed taking part in the project?

We all had a lot of fun! I’d like to think that the kids learned something new, and we definitely learned a lot from them. It felt great to give the kids the importance of contributing to the research through providing the samples: without the samples, we cannot do the experiment, without the experiments, we cannot look for more vaccines or drugs.

The comic mentions organoids, and while we didn’t go into much scientific detail, we wanted to show the children what we were going to do with the material. Their response was fantastic and they asked lots of questions after reading the comic, such as ‘what is going to happen with the samples?’, ‘how does the mini-gut work?’ and ‘how are you going to put the worms inside?’

What is going to happen with the material now?

We already have a system to study the mouse whipworm, including an animal model and mouse-derived organoids, working in-house. The organoids are a good replacement model to study the interaction of the larvae with the intestinal epithelium, and we would like to improve this approach by using human cells and human parasites. The limiting factor in this model has been the scarcity of material from the human whipworm, specifically the eggs, which is why our visit to Colombia was especially useful.

Now that we have brought the eggs to the UK, the first step is to embryonate and hatch them in special conditions. We will then start optimising the conditions to grow the worms in mini-guts of human origin.

What tips would you give to other researchers looking to get into public engagement?

When planning the engagement activity, it’s important to think not only about the idea that you want to do, but also about your target audience and how you can best approach them. For example, we initially wanted to create an educational website about the whipworm, but then realised that this wouldn’t work in a community without access to the internet or computers, so decided to create a comic book instead.

I also think it’s useful to use the support that you have around you. Universities and research institutes often have someone working in public engagement, so you can get in touch with them to work in already established projects, or bring your own ideas. I know the NC3Rs also has a public engagement awards scheme that offers funds for diverse outreach initiatives.

I am part of the STEM Ambassadors network, which has a great website and a newsletter full of amazing activity ideas every month.

Finally, what’s next for Worm Hunters?

We recently presented the Worm Hunters comic at the International Society for Neglected Tropical Diseases Festival, which showcases a wide scope of communications forms, used by health professionals and academics to tackle the current priorities in tropical disease control and global health. We were honoured to receive an award in the comic category.

We are considering repeating the project in other parts of the world. To do that, we will need to review the comic and adapt it to the local communities so that the children feel that it is really for them.

And of course, we are hoping to go back to Ciénaga next year!

Photos courtesy of Jose Angel Dianes Santos.

This project is funded by the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under a Marie Skłodowska-Curie grant and by an NC3Rs David Sainsbury Fellowship.