Housing and husbandry: Dog

Information to help refine the housing and husbandry of the laboratory dog.

On this page

Key principles

- Dogs should be socially housed with compatible individuals. Social housing should be the default.

- Enclosures should be solid-floored pen-style housing that allows the dogs good visibility of their surroundings.

- Enclosures should be arranged in a way that allows dogs to rest, eat and drink, and toilet in separate areas. Providing a choice of resting areas (e.g. shelves at varying heights) is recommended.

- Dogs should be exercised outside of their pen daily, ideally outdoors and/or in a designated enriched space.

- Every effort should be made to ensure the early rearing environment prepares research dogs for their future use.

- Positive reinforcement training should begin at a young age and can increase with complexity as the dog ages.

- Exposure to regular, positive human contact and interaction is essential for dogs of any age.

- Staff should be trained in welfare monitoring, using validated methods.

- Staff should continually review procedures and ensure that advances in the 3Rs, such as the refinement of methods, are put into practice.

Background on dog use and quality of science

Dogs (mainly purpose-bred beagles) are used in research primarily for safety, metabolic and pharmacokinetic assessment of new pharmaceuticals. Findings from dogs with compromised welfare may lead to unreliable conclusions as a result of reduced sensitivity, reliability or repeatability of data due to stress responses. Therefore it is scientifically important to be able to assess animal welfare, using robust welfare indicators, and to promote good welfare through refinement of housing, husbandry and procedures. Research staff should familiarise themselves with the literature supporting the link between good welfare and high quality data output, in order to reduce unwanted or uncontrolled variation, avoid floor or ceiling effects, and maximise the likelihood of detecting the effect under observation [1-3].

Refinement of the lifetime experience

Detailed guidance on the refinement of laboratory dog husbandry, care and use, primarily based on expert opinion, is given in the comprehensive Joint Working Group on Refinement report [3]. This key resource emphasizes the need to take into account the social, physiological and ethological needs of the dog.

There are many elements in the lifetime experience of the laboratory dog with the potential to compromise welfare, such as transport to a new facility, re-grouping, single-housing, changes in staff or the predictability of events, lack or loss of control, and performance of regulated procedures. However, there are also many opportunities to refine these aspects in order to build resilience and promote good welfare, examples of which are given below [2-8].

Housing

- Small, stable groups should be formed. Frequent changes to the group should be avoided.

- Staff should be familiar with the dynamics within home pen groups, in order to be able to change the groups if problems arise (e.g. aggression).

- There should be sufficient choice within the home pen, e.g. platforms of different types, interconnecting pens, a variety of toys and other enrichment.

- Regular access to internal and external exercise areas is beneficial to physical health and welfare but should not be substituted for other recommended refinements in the home pen.

- When dogs have increased visibility of the animal round allelomimetic barking is reduced.

- A separate area for regulated procedures is necessary to minimise disturbances and to prevent other dogs becoming distressed.

Husbandry

- Some form of positive reinforcement training should be incorporated to facilitate husbandry.

- Particular attention should be paid to the quality of interactions during husbandry and health checks, as this forms the majority of staff contact.

- If regular physical examinations or weighings are to be conducted in the same area as regulated procedures, then the same desensitisation protocol should be used.

- Rewarding calm, compliant behaviour during husbandry will facilitate training for specific procedures.

- Regular, predictable contact with assigned husbandry staff is more likely to promote good welfare than contact with unfamiliar staff.

Regulated procedures

- Desensitisation and training specific to the regulated procedures should be carried out in the pre-study period.

- Technical staff responsible for carrying out regulated procedures should be present during training to ensure desensitisation to their presence.

- Restriction to single housing should be used only when there is absolutely no alternative; in such cases, visual and olfactory contact with other dogs should be maintained wherever possible.

- Where study protocols require extended single housing, increased positive staff contact is likely to mitigate the negative effects.

- A tool for monitoring behaviour during restraint or procedures can identify dogs which are not desensitised and are exhibiting pseudo-habituation or high arousal.

- Review regulated procedures and ensure the most up-to-date refinements are used (e.g. [2]).

Recommendations for dogs held for different purposes

Many dogs used in safety assessment studies will spend the majority of their lives in the breeding facility and in holding as stock animals, with only a short amount of time spent on study. It is important that their welfare is monitored and refinements implemented before studies commence and the occurrence of aversive events which may compromise welfare. Dogs held longer term, for example those re-used in DMPK studies, may require more careful selection and more intensive welfare monitoring and desensitisation. Specific recommendations for dogs held for different purposes are given below [5-8]:

Young/stock dogs

- Regular (positive) contact with a variety of staff should be implemented as soon as possible.

- A ‘table training’ protocol to train and maintain calm behaviour will be beneficial for husbandry and future study use

- Early allocation to study groups will allow for greater acclimatisation in the pre-study phase.

- Dogs held for long periods as stock should be given additional interventions (e.g. training, enrichment) to ensure that they remain suitable as study animals.

Dogs on short term studies

- Desensitisation to staff responsible for husbandry and procedures.

- The duration and the nature of the procedures should be considered when allocating dogs.

- Dogs susceptible to the effects of single housing or regulated procedures should not be allocated to long-duration studies as the impact on welfare is likely to be greater.

- Dogs which demonstrate negative welfare in the home pen or do not respond to desensitisation and training should be allocated to non-recovery studies.

Dogs held long-term for re-use, e.g. DMPK

- Dogs which appear susceptible to negative welfare should not be selected for long-term use.

- Facilities should have criteria specific to the intended use to ensure the dogs selected will be able to cope with all aspects of the study protocols.

- Dogs held for long periods may benefit from regular contact with a small group of staff, however the loss of a familiar staff member is likely to be distressing so contact with a single member of staff only is not recommended.

- The number and nature of regulated procedures should be closely monitored to prevent cumulative severity causing negative welfare in individual dogs.

- A greater variety of enrichment opportunities will be necessary (e.g. dedicated exercise area, additional staff contact).

Housing and exercise

Laboratory dogs spend the majority of their time in their pens. The normal behaviour of the dog, and the extent to which the pen might restrict such behaviour, should be considered at the design stage [3].

In addition to providing a thoughtfully-designed main housing area, dogs should be exercised daily outside of their pen, and the use of designated exercise areas should be maximised. A well designed environment for dogs in research will:

- Facilitate social group formation and interactions with other dogs and care staff.

- Provide an open and light environment.

- Give comprehensive sight of staff outside of their pen, and visual, olfactory and auditory contact with other dogs.

- Incorporate features stimulating to the occupants and provide an element of choice and control.

- Be large enough to allow for performance of a wide range of normal behaviour (i.e. small cages are not suitable).

- Include regular access to a designated, specifically-designed exercise area, rather than just the corridor outside the dogs' pens.

As shown in the image, internal play areas provide regular access to toys and exercise equipment. Staff contact during exercise may increase desensitisation to staff and encourage appropriate behaviours.

Training and procedures

Watch our welfare webinar on socialisation and positive reinforcement training for pigs and dogs for practical examples of how positive reinforcement techniques can be applied in a research environment.

The beneficial effects of human interaction on dog behaviour and physiology are well documented [e.g. 9]. This presents opportunities to refine the experience of research dogs while also improving staff wellbeing and the quality of data output [2,6,8]. Conducting training, desensitisation and habituation requires dedicated time, however gaining the cooperation of dogs improves the ease and efficiency of carrying out husbandry and regulated procedures. Some recommendations and general principles for training dogs in a research environment are below.

Every effort should be made to ensure that staff contact is frequent and a positive experience. Periods of positive interaction between dogs and staff should be provided, to improve animal welfare, as a form of enrichment and to create a positive association with staff.

The behaviour of dogs should be shaped using rewards. Positive reinforcement training (PRT) has been successfully implemented in a number of laboratory-housed species and is a highly effective method [10-12].

A member of staff should be nominated to disseminate the principles of PRT. There is a wealth of literature available on the training of dogs using PRT [13,14]. A key member of staff should be familiar with the principles of PRT and communicate these consistently to animal care staff. This member of staff will also need designated time to ensure that they are able to stay up-to-date with PRT research.

Current habitation and training protocols should be continually reviewed to identify areas in need of refinement. For example, where habituation protocols designed to decrease fear or undesirable behaviours instead result in pseudo-habituation (characterised by a “freeze” response and spontaneous recovery of the fear response) rather than desensitisation [15].

Welfare assessment

A welfare monitoring tool in the form of a checksheet has been developed and implemented in the UK [2,16]. Using a formal monitoring tool has a number of benefits:

- It allows a single staff member to monitor the welfare of individual dogs throughout the day, over time and in a variety of contexts, and provides quantifiable data that are easily analysed.

- Staff and dogs come into frequent (and neutral) contact, allowing staff to become familiar with individual patterns of behaviour (crucial for identifying subtle changes while on study) and encourage habituation in the dogs.

- Intervention can occur before welfare becomes compromised. Examples of intervention include increasing positive interaction with staff, making changes to the group structure or home pen, or carrying out further positive reinforcement training.

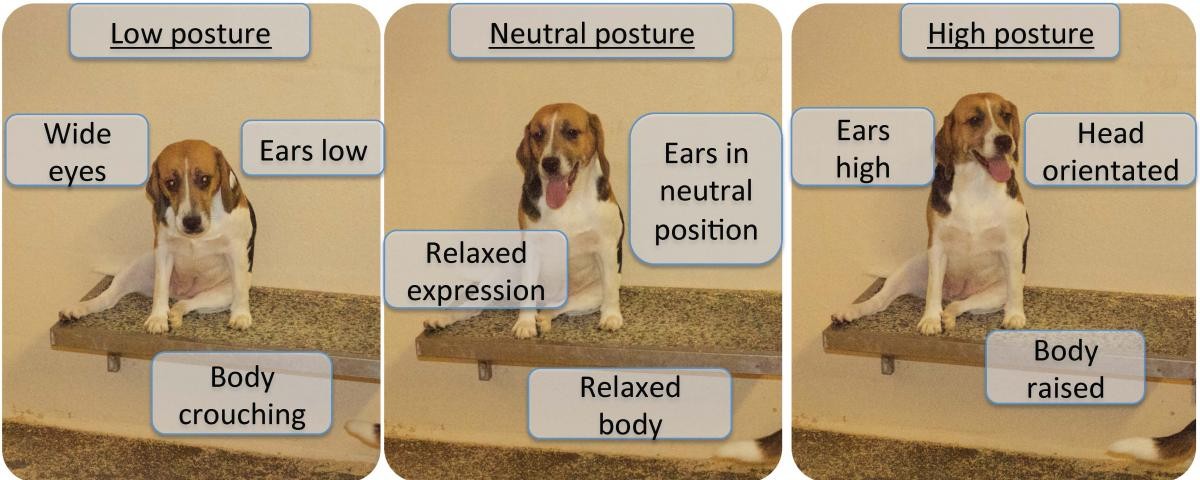

It is important that welfare-indicating behaviours are monitored throughout the day, as some negative welfare indicators will be exhibited transiently, but it is their prolonged display in the absence of stimuli such as feeding or other disturbances which is a cause for concern. All staff involved with dog studies should be familiar with:

- Indicators of positive welfare.

- Indicators of negative welfare.

- Visual signals of a dog's emotional state.

Examples of positive welfare indicators

Positive welfare indicators include:

- High posture.

- Resting.

- Amicable social behaviour.

Examples of negative welfare indicators

Negative welfare indicators include:

- Low posture.

- Prolonged vigilance.

- Pacing.

Visual signals of a dog's emotional state

Related resources

- Hall & Prescott (2021) Behavioral biology of dogs

- Scullion Hall et al. (2016) The influence of facility and home pen design on the welfare of the laboratory-housed dog

- Hall et al. (2015) Refining dosing by oral gavage in the dog: a protocol to harmonise welfare

- Meunier LD (2006) Selection, acclimation, training, and preparation of dogs for the research setting

- Prescott et al. (2004). Refining dog husbandry and care.

References

- Poole T (1997). Happy animals make good science. Laboratory Animals 31, 116-124. doi: 10.1258%2F002367797780600198

- Hall LE et al. (2015). Refining dosing by oral gavage in the dog: a protocol to harmonise welfare. Journal of Pharmacological and Toxicological Methods 72, 35-46. doi: 10.1016/j.vascn.2014.12.007

- Prescott MJ et al. (2004). Refining dog husbandry and care. Laboratory Animals 38(1): 1-94.

- Taylor K and Mills D (2007). The effect of the kennel environment on canine welfare: A critical review of experimental studies. Animal Welfare 16: 435-447.

- Fox M and Stelzner D (1966). Behavioural effects of differential early experience in the dog. Animal Behaviour 14: 273-281. doi: 10.1016/S0003-3472(66)80083-0

- Wilsson E and Sundgren P (1998). Behaviour test for eight-week old puppies - heritabilities of tested behaviour traits and its correspondence to later behaviour. Applied Animal Behaviour Science 58, 151-162. doi: 10.1016/S0168-1591(97)00093-2

- Jones A (2007). Sensory development in puppies (Canis lupus f. familiaris): Implications for improving canine welfare. Animal Welfare 16: 319-329.

- Meunier LD (2006). Selection, acclimation, training, and preparation of dogs for the research setting. ILAR 47: 326-347. doi: 10.1093/ilar.47.4.326

- Vormbrock JK and Grossberg JM (1988). Cardiovascular effects in human-pet dog interactions. Journal of Behavioral Medicine 11(5), 509-517. doi: 10.1007/bf00844843

- Laule GE et al. (2003). The use of positive reinforcement training techniques to enhance the care, management, and welfare of primates in the laboratory. Journal of Applied Animal Welfare Science 6(3), 163-173. doi: 10.1207/S15327604JAWS0603_02

- McKinley J et al. (2003). Training common marmosets (Callithrix jacchus) to cooperate during routine laboratory procedures: ease of training and time investment. Journal of Applied Animal Welfare Science 6(3), 209-20. doi: 10.1207/S15327604JAWS0603_06

- Prescott M and Buchanan-Smith H (2003). Training nonhuman primates using positive reinforcement techniques. Journal of Applied Animal Welfare Science 6(3), 157-161. doi: 10.1207/S15327604JAWS0603_01

- Pryor K (2002). Don’t shoot the dog! The new art of teaching and training, 3rd Edition. Lydney: Ringpress Books Ltd.

- Hiby EF et al. (2004). Dog training methods: their use, effectiveness and interaction with behaviour and welfare. Animal Welfare 13: 63-69.

- Ruys JD et al. (2004). Behavioral and physiological adaptation to repeated chair restraint in rhesus macaques. Physiology and Behavior 82, 205–213. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2004.02.031

- Hall LE et al. (in prep). A welfare assessment framework for the laboratory-housed dog.