Making refinements a reality – why we can be proud

Animal care staff at the University of Dundee's Medical School Resources Unit (MSRU) have put a number of refinements into practice over the past 18 months, including improving environmental enrichment and refining their breeding colonies.

In this guest blog post, animal technician Joanne King shares some of these changes and how they've made a difference.

This piece was originally published in the August 2019 edition of Animal Technology and Welfare under the title "Team Awesome – why we can be proud".

Introduction

The presentation I gave at IAT Congress 2019 was based on the changes and refinements the MSRU has made over the past 18 months.

New homes from old

The first change we made was to the housing of our guinea pigs. The old cages (Figure 1) were small open topped cages. Five animals were housed in these cages, so there was not much floor space for them to run around and no room to add extra enrichment.

Figure 1. Old guinea pig cages.

One of our vacant rooms was used to create a floor pen for the animals using redundant materials lying around the unit, old sizzle nest boxes, tubes and boxes (Figure 2). The fronts of the old cages were used to create a secure structure for the food hoppers and water bottles. We housed ten guinea pigs in this room and saw a difference in their behaviour almost immediately: they were more inquisitive and would approach technicians willingly, apparently without fear. They were also easier to handle and generally happier – as indicated by their persistent “popcorning” (sudden and erratic jumping behaviour associated with excitement and happiness in guinea pigs, so called because it resembles corn being popped) – and happy piggies equals happy technicians.

Figure 2. New floor pen.

Refinement of breeding colonies

The refinement and reduction of our rat breeding colonies was something we were particularly proud of, as this change made a huge impact on the lives of our animals.

The old system consisted of two separate colonies, one for each researcher who used the rats. The females and males lived in separate cages, only coming together to mate. Figure 3 shows the timed mating grid boxes the animals were placed in. They could be in here for up to seven days or until a plug had been found at the bottom of the cage.

Figure 3. Gridded floor time-mating cage.

There were many problems with the old system:

- Animals were singly housed.

- Researchers refused to share one colony, meaning there was a huge amount of surplus pups.

- Welfare issues with regards to the grid bottomed boxes.

- Approximately 15 females breeding in each colony, with three males on rotation, three matings established each week.

- Animals were difficult to handle and aggressive.

- Small litters and short breeding life.

New breeding stock, both males and females, were purchased and housed as monogamous pairs when it was suitable. We did not charge the researchers for this as we knew we had to first convince them it was the way forward and best course of action. Taking into consideration the date they were mated and also when we could see they were pregnant, we were able to determine when females would litter down with one to two days margin of error. This was satisfactory for the needs of the users. The litter sizes had increased and we found the animals in the pairs were easier to handle and friendlier.

Although we had convinced the users to change the method of breeding and to share one colony, we encountered a number of problems following the change. The standard open top cages we use to house our animals were not suitable for monogamous pairs and their large litters. At times there could be up to 21 animals in the box, meaning the cages needed to be cleaned at least twice a week, and there was a problem with overcrowding and the females over-grooming themselves. Some had completely removed all hair on their upper body including their forelimbs.

With the help of our very handy washroom supervisor Jim, we were able to combine two standard cages using a standard red tube and drilling holes into the cages so the tube can connect them (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Boxes connected by tube.

The animals now had a lot more space to move around the cage and to care for their pups. The females stopped over-grooming, but despite being paired at different times, all of them began to give birth within a day or two of one another, which was no good to us.

It was then decided to remove the male before the female littered down in order to avoid post-partum oestrus with males being re-introduced later, to once again stagger parturition.

We quickly learned that this was not ideal as the male showed aggression towards his pups and the female meaning that we could not place him back in his cage until all the pups had been weaned. This would have resulted in our needing more breeders to compensate for the gaps. To avoid this, we inserted a clear disc with holes drilled in the middle of the red tube connecting the two boxes (Figure 5), which allowed us to separate the male and female when needed but still allowed them to smell and see each other whilst apart, which in turn stopped the aggression.

Figure 5. Perspex insert for separation of cages.

Eventually we arrived at a system which worked for us and the researchers. The animals were no longer aggressive or alone, they now have larger cages and are not being confined to the small timed-mating cages. The pairs are producing larger litters consistently and the animals have better welfare, which of course equals better science.

Improved environmental enrichment

At the MSRU we are progressing and experimenting with enrichment. The code of practice provides no standardisation – it strongly recommends enrichment such as tunnels, boxes and climbing apparatus, but does not enforce it. This is why there are such large discrepancies between units.

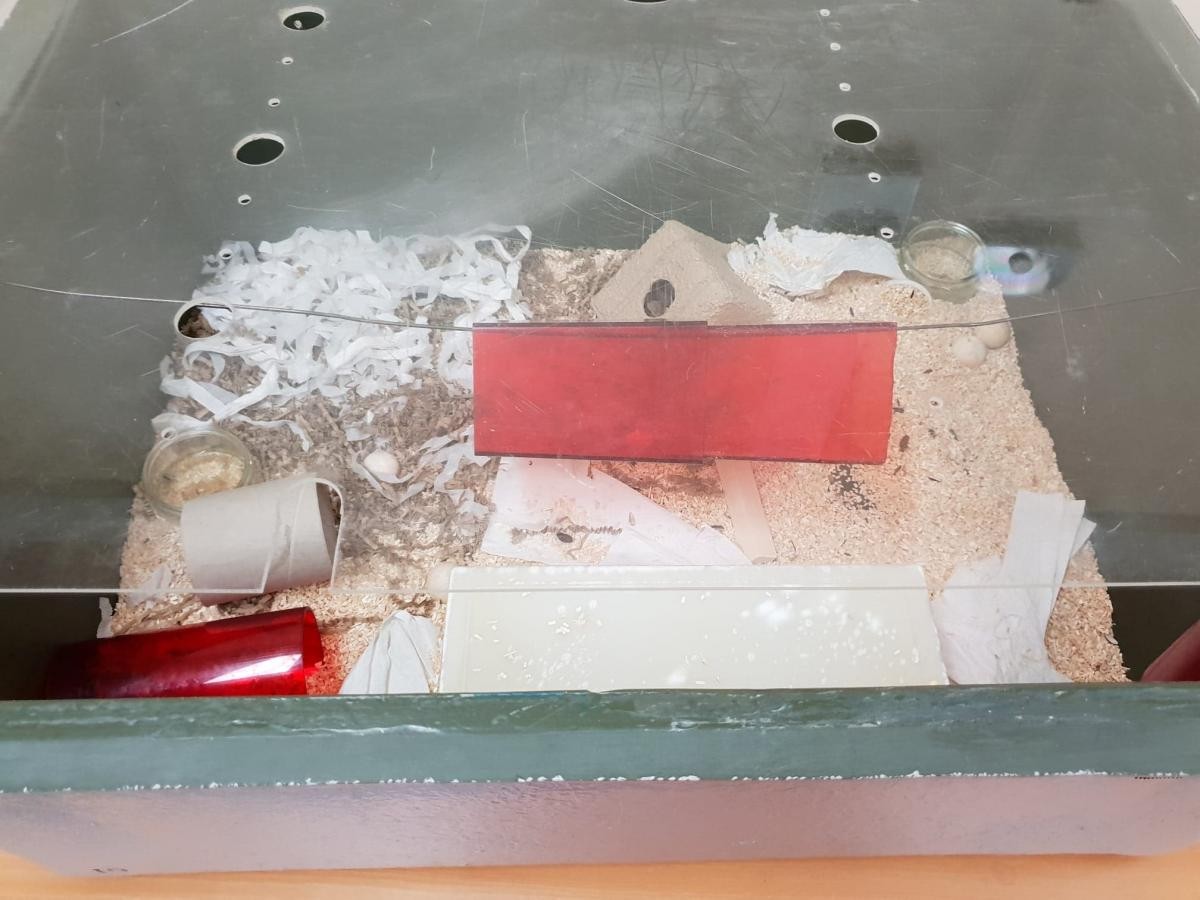

The MSRU's standard cage receives a house or tunnel, foraging diet, chew-sticks, sizzle nest and paper wool. The extra enrichment we provide includes tunnels or houses on the roof, paper towels through the bars, aspen balls and cubes, swing or cable ties and nestlets. We add this mainly to reduce barbering and fighting animals but we provide it to other animals where and when we can.

Figure 6. An 'enriched' cage.

Figure 6 shows a cage where the animals have been heavily barbered: we placed almost every bit of extra enrichment we could in it. In this case the approach gave good results: within a few weeks all the mice had grown back their hair. However, not all cages were as successful, and in some cases the enrichment made no difference at all.

We came to realise through the efforts of other units in Dundee that not all mice like the same enrichment. C57Blk/6 and Balb/c especially have very different preferences when it comes to swings and chew-sticks as well as the placement of their enrichment in the cages.

Rotation of the enrichment seems to help, adding different items each week to the cages at cage change. Once an item has been in the cage for a while it becomes part of the standard cage, which is acceptable if the problem is fixed in a short amount of time. In the case of fighting, this should stop in a very short amount of time, otherwise the animals must be separated. With barbering, it may take a little longer to see any improvement so rotation of items in the cage is ideal.

Further investigation is needed to determine the effectiveness of enrichment on barbering and fighting. Carrying out preference testing beforehand would be a good idea as there is no point in adding enrichment to cages if the mice do not like it.

Doing our best

Our goal at the MSRU is the same as all animal technicians: to make the lives of the animals under our care as painless and as comfortable as possible within the scope of the scientific requirements. We obtained surplus Lister hooded rats, which we decided to keep for training others in handling. Using the same techniques as the breeding rat cages we joined three cages with the red tubes to give them extra living space (Figure 7).

Figure 7. Three combined cages.

We have also trialled new treats for the rats as we feel the standard sunflower seeds provide little challenge for them. However, peanuts still in their shell (known as monkey nuts) were a big hit with them (Figure 8). We have started ordering them from our suppliers and adding them to the cages at cage change on a weekly basis.

Figure 8. Rats enjoying monkey nuts.

Before we cannibalised the cages to give the rats more space, we would place the rats in playpens for a few hours a day, to give a little more exercise and room to play. Now that the increased floor space in most of the rats' cages supersedes that of the playpen and we can add extra enrichment, we mostly use them when we need to amalgamate groups of animals. Playpens provide a neutral territory, so we have found this method extremely successful. Again, the playpens were created by Jim, using materials we had lying around the unit and old toad tanks (Figure 9).

Figure 9. Playpen made from old toad tank.

Changing our ways

The way we handle the animals is now changing and at the MSRU all staff and users of the unit have successfully moved from the traditional method of tail handling to tubing and cupping. As with any change it was met with some resistance, but through perseverance we prevailed. The initial change was time-consuming for the technicians as neither they nor the animals were used to the method of handling. After some practice there was very little time difference when changing boxes when compared to the old method. Once the animals were used to the new method they too were a lot more relaxed when handling, so much so that there was no need to restrain the tail when cupping (Figure 10). There is a lot more interaction between the technician and the animals handled using this method, which is much more rewarding.

Figure 10. Mouse calm and unrestrained.

As mentioned previously, the rats receive two different type of nesting material, paper wool and sizzle nest. Having learned from our Named Veterinary Surgeon (NVS) that a recent paper highlighted how rats in the wild use coarser nesting materials such as sticks and foliage, we decided to introduce some hay at cage change to see if our rats would use it in their nests. The majority of the animals ate it and the only ones to use the material in their nest were the breeders. Therefore, we continued to only give the hay to the breeders at cage change.

Rehoming animals

After a behavioural study ended, we had 34 adolescent Lister hooded rats which were to be euthanised. This seemed inappropriate, so we made posters in the unit asking if anyone would like to take them home as pets. We received a lot of interest and eventually we were able to rehome 30 of the animals, keeping the remaining four females for handling. The process took a few weeks, with Home Office approval and our NVS helping the recipients who did not have much knowledge or time with the rats. No one likes wasted animals, especially on this scale, and we are very proud of the fact we re-homed 30 of the rats. We hear regularly from their owners that they are doing well.

Onwards and upwards

We are a proactive unit, taking part in the Institute of Animal Technology's Tech Month in March 2019, where we had Tech Tea with all our users and ran a raffle making over £200. We used this money for various things during Tech Month such as prizes for the treasure hunt and animal trivia bingo for the users and technicians. We also had a little gathering in the seminar room where we had a presentation from a Tecniplast representative, who sponsored a tech dinner at a restaurant the same day.

We are also planning to carry out two studies: the first will be preference testing the enrichment and the second will be the effect enrichment has on aggression and barbering.

We at the MSRU are most proud of our ability to change and adapt. Change will never be easy and will never go to plan, but the important thing is to not revert back to old habits or to just be satisfied with the way things are because they've always been like that and it works. Just because something has worked for a long time, it does not mean there is not a better, more refined way to do things. Whether it is changing handling methods, housing conditions or enrichment, change will always be difficult, but with any problems which arise, solutions must found. You must remember you are making the change for a reason.